This article was originally printed on Inside Passage, April 3, 2017. It is a blog maintained by the Puget Sound Maritime Historical Society. It was researched and written by Eleanor Boba, A link to their site will be added at the end of the article where many other articles of local historical interest may be found.

Snagboats on Puget Sound: A Photo Essay

For the full story of the Puget Sound snagboats, read Ron Burke's detailed and beautifully-illustrated article for The Sea Chest -- "Heritage of a Snagboat" (June 2001).

|

The snagboats Skagit and Swinomish side by side in 1915. Their A-frame cranes sit on the bows.

Photo, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.

|

WHOOPIN' IT UP!

In a 1981 interview, Sandy Welsh Jr. explained that the Preston ended up with the whistles of both earlier snagboats, as well as its own:The two big steam whistles from the Swinomish and the Skagit, they operated together. Mine was, well I call it a whooper, and it was kind of a steam siren. I operated it independently. You could kind of play a little bit of a tune with them both going. We had a lot of fun. There was a couple other steam boats that had whooper sirens on them. We would whoop back and forth.

People really get a thrill out of listening to the steam whistles. You'll go by, like through the Lake Washington Ship Canal, and people will come out of their offices or on the boat next to you and yell, "blow the whistle, blow the whistle.“ I'll always give an extra toot for a thank you for each of the bridges we go through. Most of the time the bridge tenders will give a little toot back in answer. Especially Bill, who works on the Ballard Bridge up there, he says, "how about a real long one with the bridge opening?" So, I'll give him a little bit extra long one because he really likes to hear the steam whistle. It's really funny though. You'll just see the people, and if you can't hear them you'll just see the arms pump up and down. "Blow that whistle!“ (Oral History, Virgil (Sandy) V. Welsh Jr., Second Mate and Caption on the Preston, 1975-81. From the archives of the Anacortes Maritime Heritage Center)

BURNING DOWN THE HOUSE

|

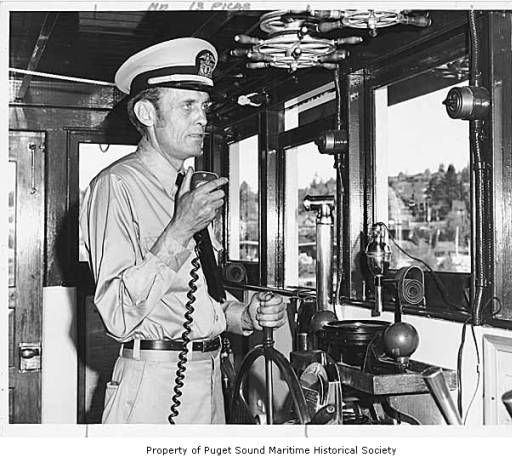

Captain William M. Morgan at the helm of the W.T. Preston, 1975.

Photo, Puget Sound Maritime Historical Society.

|

Captain William W. Morgan told Pam Negri about part of the job that involved burning derelict houseboats:

We used to do quite a bit of work in conjunction with the Seattle Harbor Patrol. They would assist us, either bring in snags or tell us where they were at. Anyway, we were burning a considerable amount of houseboats, and they were the ones that were towing the boats down to Montlake across from the old canoe house at the U.W. There were times when we would have a half-dozen houses. We would burn them right down to the logs, then pick the logs up and set them on the beach.

This one particular time, we used to go in and open the valves or break the water lines so there was no water remaining to cause any possible explosions. We'd gone through this one house and broke a few lines, opened all the valves we could see. Then we set our fire. Well, it was really burning pretty good. The old tar paper roofs-everything was really going strong. Here comes a harbor police boat heading toward the shore-must have been an emergency. We were all standing on our deck, watching this houseboat burn when all of the sudden there's this terrific explosion. Here goes this hot water tank, shooting out across the water, landing right in front of this police boat coming full out towards it. It was pretty funny at the time, but could have been extremely serious.

[The Harbor Patrol] kind of laughed it off. Particularly one of them that I knew quite well, he said, "Wouldn't that look good on the front page of the PI [Post-Intelligencer], Preston torpedoes Seattle police boat with hot water tank." (Oral History, William W. Morgan (Tape 16), Deckhand, First Mate, Second Mate, and Captain 1952-1982. From the archives of the Anacortes Maritime Heritage Center)

COWS ON THE BRINK

Norman Hamburg began his career as a cabin boy on the Swinomish in 1927 and later transferred to the Preston. In his 1982 interview he told Pam Negri about one little-known aspect of the work:

A lot of times there was a lot of erosion along the [river] banks. The cows would get too close to the edge of the bank eating grass, and sometimes the bank would cave in and down would go the cow in the river. We picked up quite a few cows in the river, set them back down on the bank for the farmer. [How?] Put a rope sling around 'em, just behind their front legs and just ahead of their rear legs, picked 'em right up with the donkey engine and swung them over and set them on the bank. They very seldom hurt themselves; they landed on the soft mud in the river there. (Oral History, Norman Hamburg (Tape 10), January 15, 1982. From the archives of the Anacortes Maritime Heritage Center)

Crew of the W.T. Preston, 1939. U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.

WARTIME

Hamburg explains the effect of World War II on the snagboat business:

During World War II, when they stopped all river and harbor work, they tied the Preston up at the locks wall. They transferred all the laid-off crew that didn't have 15 years of service in. They found other jobs for them, but what I mean [is] they were laid off the Preston. They kept the captain, the chief engineers, myself and the cook. We stayed aboard the vessel for quarters and helped keep the vessel in shape, and we were transferred over to the locks. The chief engineer and I were transferred over to the machine shop -- working for Charlie Seagren. We were outfitting boats for Alaska and a lot of the boats were going up to [Adak?] Island, building the airbase up there. Also, the Alcan Highway [Alaska-Canadian]: we did a lot of work at the locks for the Alcan Highway making different things in the machine shop and the blacksmith shops. They didn't bring the Preston out until after World War II....but they kept us crew aboard in case some emergency would arise.

I remember when we came to work on December 8th [1941]; it was on a Monday morning. Driving down from Mount Vernon, we were stopped at the main gate going in -- soldiers galore. Went through our suitcases. They went through our luggage and they walked with us down to the Preston to get verification that we belonged to that crew. Our cook -- little Fritz -- fed about, I'd say, 30 soldiers for the meals on the Preston until they had facilities built and they built barracks down at the locks for these soldiers to stay in because they were on guard there -- on duty 24 hours a day. The barracks at that time were built on a wall just west of the administration building.

One of the first jobs the snagboat had was to lay a cable across from the small locks over to the south end of the spillway to hang a netted, mesh fence on there to stop anything that could drift down to blow up the spillway. Everything was very vulnerable. They had blackouts for all the sawmills, the homes, the street lights -- everything had to be turned out at dusk and you had dark blinds over your windows in the homes. There was absolutely no light on the west coast at all, until they found out just how vulnerable it was. They were afraid of a Japanese attack on the west coast.

There were a lot of boats tied up in Lake Washington and Kirkland in the area.....Lake Union....and if something would have happened to the locks there, it would have drained the water out of Lake Union and been a real disaster. (Ibid.)

|

Coast Guard barracks and mess hall at the locks, August 14, 1943.

Photo, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.

|

-- Eleanor Boba